- Home

- Mortimer, Ian

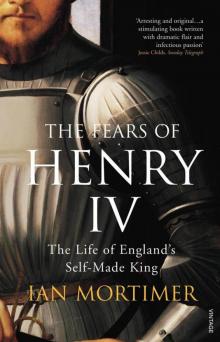

The Fears of Henry IV: The Life of England's Self-Made King

The Fears of Henry IV: The Life of England's Self-Made King Read online

CONTENTS

Cover

About the Book

About the Author

Praise

List of Illustrations

Genealogical Tables

The English Royal Family before 1399

The Lancastrian family network

The English Royal Family after 1399

The French Royal Family

Author’s Note

Dedication

Title Page

Introduction

The Hatch and Brood of Time

All Courtesy from Heaven

The Summons of the Appellant’s Trumpet

Iron Wars

As Far as to the Sepulchre of Christ

Curst Melancholy

By Envy’s Hand and Murder’s Bloody Axe

The Breath of Kings

The Virtue of Necessity

High Sparks of Honour

A Deed Chronicled in Hell

The Great Magician

Uneasy Lies the Head

A Bloody Field by Shrewsbury

Treason’s True Bed

Smooth Comforts False

Golden Care

In That Jerusalem

That I and Greatness were Compelled to Kiss

Picture Section

Notes

Appendices

Henry’s Date of Birth and the Royal Maundy

The Succession to the Crown, 1386–99

Henry’s Children

Casualties at the Battle of Shrewsbury

Henry’s Speed of Travel in 1406 and 1407

Henry’s Physicians and Surgeons

The Lancastrian Esses Collar

Acknowledgements

Select Bibliography and List of Abbreviations

Index

Copyright

ABOUT THE BOOK

In June 1405, King Henry IV stopped at a small Yorkshire manor house to shelter from a storm. That night he awoke screaming that traitors were burning his skin. His instinctive belief that he was being poisoned was understandable; he had already survived at least eight plots to dethrone or kill him in the first six years of his reign

Henry had not always been so unpopular – in 1399, at the age of thirty-two, he was greeted as the saviour of his realm after ousting the insecure and tyrannical Richard II. But, surrounded by men who supported him only as long as they could control him, he was soon transformed from a hero into a duplicitious murderer; a king prepared to go to any lengths to save his family and his throne.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ian Mortimer has BA and PhD degrees in history from Exeter University and an MA in archive studies from University College London. From 1991 to 2003 he worked for Devon Record Office, Reading University, the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts, and Exeter University. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society in 1998, and was awarded the Alexander Prize (2004) by the Royal Historical Society for his work on the social history of medicine. He is the author of two other medieval biographies, The Greatest Traitor: The Life of Sir Roger Mortimer and The Perfect King: The Life of Edward III, published in 2003 and 2006 respectively by Jonathan Cape. He lives with his wife and three children on the edge of Dartmoor.

‘Mortimer has amply demonstrated his ambition as a historian. His book offers a wealth of challenging new insights into this fascinating but enigmatic ruler’

The Times Higher Education Supplement

‘Conventional wisdom claims that a ‘proper’ biography of someone from the medieval era is an impossibility. Too little evidence survives of the kind required to reconstruct a personality. In his remarkable life of England’s first Lancastrian King, Mortimer proves that wisdom wrong. Through subtle and imaginative use of primary sources … he has created not only a compelling narrative of a significant period in English history but also a convincing portrait of a complex and contradictory man’

Sunday Times

‘Mortimer argues effectively for an appreciation of a complex man … He writes with considerable verve and skill, unlocking numerous fascinating historical details from a thorough study of Henry’s surviving account books … The historian will welcome Mortimer’s trilogy of biographies, the general reader will appreciate this one in particular, as will any student of Shakespeare’

The Book Magazine

‘A full and richly detailed life … a fine biography’

Spectator

‘He has made fuller and more effective use than any other historian of the unpublished material in the records of the Duchy of Lancaster. He has an instinctive sympathy for the men about whom he writes, a real understanding of the mentalities of late medieval England, and a vivid historical imagination which lends colour and excitement to his pages … McFarlane observed in his lectures that if Shakespeare had focused on the personality of Henry IV, he would have come up with a more complex Macbeth. Mortimer has avowedly set out to write about the more complex Macbeth that Shakespeare never gave us’

Jonathan Sumption,

Literary Review

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Henry, first duke of Lancaster (The British Library, Stowe $94, fol. 8).

Edward III with the Black Prince (The British Library, Cotton Nero D.VI fol 31).

The lost tomb of John of Gaunt and Blanche (author’s collection).

Bolingbroke Castle (author’s collection).

The Black Prince (Canterbury Cathedral).

Mary Bohun and her mother, the countess of Hereford (The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, MS Auct. D. 4. 4. fol. 181v).

Sixteenth-century portrait of Henry IV, now discredited (National Portrait Gallery, NPG 4980(9)).

Henry IV, c.1402 (The National Archives, Great Cowcher of the duchy of Lancaster, DL 42/1–2).

Richard II (The Dean and Chapter, Westminster Abbey).

Edmund, duke of York (The Dean and Chapter, Westminster Abbey).

Henry presenting Richard II to the citizens of London (The British Library, Harley 1319, fol. 53v).

Pontefract Castle (Bridgeman Art Gallery).

Conway Castle (author’s collection).

Henry and his eldest son beside the empty throne (The British Library, Harley 1319, fol 57).

Henry IV and Prince Henry, c.1402 (The National Archives, Great Cowcher of the duchy of Lancaster, DL 42/1–2).

Thomas, duke of Clarence (Canterbury Cathedral).

Ralph Neville, earl of Westmorland, and his second wife, Joan Beaufort (Dr John Banham).

John Beaufort, earl of Somerset (Canterbury Cathedral).

Henry Beaufort, bishop of Winchester (author’s collection).

Henry’s seal as duke of Lancaster in 1399 (author’s collection).

The Black Prince’s seal in 1362 (author’s collection).

Henry’s second great seal (author’s collection).

The Dunstable Swan Jewel (The Trustees of the British Museum).

Blanche’s crown (Bayerische Verwaltung der staatlichen Schlösser, Gärten und Seen, Munich).

The coronation of Queen Joan (The British Library, Cotton Julius E.IV art. 6 fol. 2v).

Henry IV and Queen Joan [Adrian Fletcher, www.paradoxplace.com).

Archbishop Thomas Arundel (The British Library, Harley 1319, fol. 12r).

Battlefield Church, Shrewsbury (author’s collection).

Lancaster Castle gate (Lancashire County Museums).

GENEALOGICAL TABLES

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Although most members of the English royal family were given their place of birth as a surname by chroniclers wishing to distinguish one Henry

or one Edward from others of the same name, it was rare for a member of the royal family to adopt his place of birth as a part of his official identity. The earliest references to Henry being referred to as ‘Henry of Bolingbroke’ are historical: namely, the sections of the fifteenth-century continuation of the Brut chronicle (written about 1430) and his entry in John Capgrave’s book The Illustrious Henrys which was written a little later. In all official documents for the period 1377–97 he is ‘Henry of Lancaster, earl of Derby’ or ‘the earl of Derby, son of the duke of Lancaster’, or a variation on one of these. His own household account books bear the name ‘Henry of Lancaster, earl of Derby’. This is also the name by which his father addressed him in official letters and the way his father’s treasurer described him in his accounts. The contemporary chroniclers Henry Knighton, Thomas Walsingham and the Westminster chronicler all consistently refer to him as ‘Henry of Lancaster’, and in claiming the throne he referred to himself as ‘I, Henry of Lancaster …’. Although the indexes to the Oxford University Press editions of the contemporary chronicles all say ‘Henry earl of Derby: see Bolingbroke’ this style of nomenclature is anachronistic. It is also impersonal, comparable to describing Prince Henry as ‘Monmouth’ or Duke Henry of Lancaster as ‘Grosmont’. As a result of this, the name ‘Henry of Lancaster’ has been used throughout this book. Where appropriate, the same format has been followed with regard to his father’s name, although ‘John of Gaunt/Ghent’ was an occasional contemporary appellation in his case.1

With regard to other names, most English surnames which include ‘de’ in the original source have been simplified, with the silent loss of the ‘de’. Where it remained traditionally incorporated in the surname (e.g. de la Pole, de Vere) these have been retained. ‘De’ has generally been retained in French names.

The first names of members of the French royal family have been Anglicised. French forenames otherwise have been left in the standard French form.

With regard to Aquitaine, the term ‘Gascony’ has normally been used in a generic sense to mean all the English Crown’s possession in southwest France.

This book is dedicated to my mother, Judy, mindful of the fact that Henry IV never knew his mother.

In one respect, at least, I have been more fortunate than a king.

IAN MORTIMER

The Fears of

Henry IV

The Life of England’s Self-made King

VINTAGE BOOKS

London

INTRODUCTION

Shakespeare has a lot to answer for. While historians today might argue about the significance of the end of Plantagenet rule in 1485, and whether terms such as the Hundred Years War and the Wars of the Roses serve any useful purpose, Shakespeare has dictated the most important cut-off date in English medieval history: 1397. Quite simply, that is the historical point at which his great cycle of history plays begins. It is therefore the start date for our collective familiarity with the leading characters from British history. The well-educated modern reader is familiar with the idea of Richard II and Henry IV as eloquent, intelligent and sophisticated individuals in a way he or she is not with their predecessors. We all know the name of John of Gaunt – ‘Time-honoured Lancaster’ as he appears in Shakespeare’s Richard II – but few people recall his father-in-law, the first duke of Lancaster, a more brilliant man in almost every way. The psychological characteristics of political figures before 1397 are known only to those who have studied them whereas, because of Shakespeare, we believe that the English royal family after 1397 was a crucible of glory and terror, and that its individual representatives changed the course of English history through their personal loves, fears, ambitions, vision and courage.

Shakespeare, however, was not a historian. His themes were exclusively living themes: the human struggle against the ‘slings and arrows’ of personal misfortune and the causes and consequences of political revolution. He was not concerned with accurate descriptions of past individuals or events. He also had little or no understanding of the social and religious differences between the early fifteenth century and his own time. We only have to remind ourselves of his failure to mention the Peasants’ Revolt to appreciate that his play about Richard II is not an attempt to provide a full picture of the king’s life. Although there are elements of Shakespeare’s fictional Henry IV which are closely related to the historical king, the result is an inevitable distortion of his personality and career. In short, the popular view of Henry IV is mainly an Elizabethan embroidery incorporating a few golden threads of historical detail. Henry IV may be a key figure in no fewer than three of the greatest history plays ever written but, as an individual, he lurks in the shadows of the popular imagination, as if still cautious of the judgement of other ages, hardly ever emerging to proclaim himself as the man he was, or openly to explain himself and his actions.

The image of Henry lurking in the shadows of the late middle ages is a good one with which to begin a study of him, for he is perhaps the most enigmatic of all the post-Conquest rulers of England. The great nineteenth-century historian William Stubbs declared that ‘there is scarcely one in the whole line of our kings of whose personality it is so difficult to get a definite idea’.1 Indeed, one of the reasons Henry was so useful to Shakespeare is his very obscurity. In the playwright’s hands he could be Bolingbroke, the ruthless commander and ambitious usurper, and yet he could also be King Henry, ‘mighty and to be feared’, yet somewhat aloof and unengaging, being too full of majesty. This is not a sign of attention to him as a man but rather to his station, as a duke or king. There is no attempt to portray the Bolingbroke/Henry IV characters as having any key trait in common. In 1596 (the year in which Henry IV Part One was written) no one had any in-depth understanding of the man’s personality. As the historian K. B. McFarlane pointed out, the Tudors in general – and Shakespeare in particular – ignored Henry, and that proved fatal to his historical reputation.2

The Tudors had a good reason to ignore Henry, as demonstrated in the career of the one man who did not ignore him. This was Dr John Hayward, a Cambridge-educated doctor of law, who in 1599 published a historical study entitled The First Part of the Life and Raigne of King Henrie IIII. It was immediately both popular and vilified.3 The first edition of a thousand copies sold out, but it came to the attention of the queen, Elizabeth I, who saw in it an attempt to compare her with Richard II and to justify her deposition. This was largely paranoia on the aged queen’s part, who is supposed to have declared in her fury ‘know ye not I am Richard II?’. Nevertheless, she sought to have the author arraigned for treason, and Hayward was accordingly locked up in the Tower of London for daring to write ‘a storie 200 yere olde’. The second edition was banned, seized and burned. With that sort of review, all prospective publishers were persuaded that The Second Part (up to 1403) was far too dangerous to print, and the third part was never written. Indeed, the whole experiment in writing about the man who deposed Richard II was seen to be so controversial that no one attempted to follow Hayward’s example until absolute monarchy was well and truly a thing of the past.

As a result, it is only in recent times that historians have begun to move closer to the historical Henry IV. In 1878, William Stubbs published the third and final volume of his landmark work, The Constitutional History of England. In seventy-four pages he provided his readers with an overview of Henry’s reign which was both new and positive. Unlike any previous historian, Stubbs presented Henry as ‘a great king’, albeit troubled at every stage of his reign.4 The reason for his greatness was only partly because he founded a dynasty; mainly it was because (according to Stubbs) he initiated ‘a great constitutional experiment, a premature testing of the strength of the parliamentary system’.5 Stubbs was particularly impressed by the fact that ‘there [was] much treason outside but none within the House of Commons’. This led to his conclusion that, by the time of his death, Henry IV ‘had exemplified the truth that a king acting in constitutional relations with his parli

ament may withstand and overcome any amount of domestic difficulty’.6

It has to be said that this is ‘greatness’ as defined by Stubbs, not as understood by Henry’s contemporaries. In the fifteenth century it was Henry’s grandfather, Edward III, who was regarded as the model for greatness: a man who took the war to France and Scotland and won, and who presided over peace at home for half a century. Henry IV was not deemed ‘great’ by his contemporaries for the simple reason that he failed to live up to this example. But even if we go along with Stubbs and accept that a man can be retrospectively ‘great’ because his constitutional ambitions come into vogue four centuries after his death, we still have a problem in that Stubbs assumed that constitutional achievements necessitate constitutional ambitions. They do not. Some of the most important parliamentary developments of the middle ages were achieved in spite of royal participation, not because of it. Indeed, as this book will show, Henry’s vision of kingship was substantially based on that of Edward III, and he approached parliament with a largely conservative agenda. The question of whether or not Henry was a great king in the fifteenth century, or subsequently, is a distraction. A man’s character may be obscured as much by the acclamation of greatness as by neglect.

Stubbs’s slightly younger contemporary Dr James Hamilton Wylie took the opposite approach to Stubbs. Rather than describing Henry’s reign in the context of the development of the constitution, Wylie looked at the administration of England in the context of the reign. The History of England under Henry the Fourth, published in four volumes between 1884 and 1898, is an astounding compendium of facts, showing very wide reading on the part of the author and containing many perspicacious judgements. It was also a pioneering work: no one had previously given so much attention to a period of just thirteen years before 1500. It includes a great deal of information about the king and many notes from his accounts prior to his accession, and remains the most complete chronology of the reign even today. However, it is first and foremost a history of England, not a biography, and so there is little or no attempt to reconcile the king’s actions, writings and reported statements, or to present a coherent portrait of the man. And there are so many highly detailed digressions that at times it is difficult to remember where we are in Dr Wylie’s narrative. Those searching for Henry’s character will struggle to find it amid the tangled and seemingly endless documentary undergrowth.

1415: Henry V's Year of Glory

1415: Henry V's Year of Glory The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England

The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England The Fears of Henry IV: The Life of England's Self-Made King

The Fears of Henry IV: The Life of England's Self-Made King